Artifact from the Mitigation of Shock project. Image: Superflux

Blog

Climate crisis: Why Swiss cities should dare to experiment with the future

This article was originally published in German on medium.com. In Switzerland, too, cities need to become climate-neutral quickly. But the complexity of the climate crisis seems to lead to impotence and an inability to act. Future experiments can provide a remedy here.

The key role of cities

With their high population density, cities play a key role in the necessary system change. Today, more than half of the global population already lives in cities - and the trend is rising. It is therefore imperative that cities become climate neutral so that we can ensure our survival on planet Earth.

In Switzerland, too, cities are responsible for the largest CO₂ emissions. They therefore bear a particularly large responsibility while having enormous potential to accelerate the change toward a climate-neutral society. Cities such as Bern, Basel or Zurich have set themselves more ambitious climate targets than the federal government. But are cities equipped to achieve these goals?

Paralyzed by complexity

There is a growing awareness of the need for action in politics, society and business. Political targets have been set (e.g. Zurich net zero by 2040), but implementation is faltering. Switzerland is not on track and has missed its climate targets by 2020 in almost all sectors.

The responsible actors do not seem to have found sufficient means yet. This is not surprising, because the climate crisis is a "Wicked Problem". In other words, a problem that consists of complex interactions and for which there is not one solution.

"Wicked" also means that solving one aspect can lead to new problems. For example, if cities install charging stations for e-cars everywhere, electric-powered vehicles become more attractive. At first glance, this seems to make sense, because it reduces CO₂ emissions from automobile traffic. However, if everyone now buys e-cars, a lot of gray energy (energy for the production of the vehicles) will be generated and far more green energy will have to be produced than before. In addition, a large part of the city would remain occupied by parked cars, leaving no space for the transformation of the city due to climate change (e.g. parks, shadows, bike lanes). It is therefore questionable whether the excessive expansion of charging stations in the city is a sustainable solution.

Decision makers are often confronted with such dilemmas and conflicts of interest. If the right strategies for a systemic problem analysis and an adapted approach are missing, this can lead to excessive demands and inability to act.

So where should we start? One methodology that can free us from our inability to act is experimentation.

Experiments as accelerators

With its experiment "Bring's uf d'Strass", for example, Zurich has tested the diverse uses of neighborhood streets and climate-adapted urban design. In the summer, streets were temporarily closed to cars and redesigned for recreation and encounters.

Experiment «Bring’s uf d’Strass!» in Zürich. Bild: Stadt Zürich

Instead of transforming the city in one go with a large master plan and relying solely on theory, a possible future is tested on a small scale. From this, important experience can be gained for scaling up. Does the future also lead to the desired results in reality? How does the population react to it? What could be improved?

Below we explain what "future experiments" are and what they are good for.

Making futures tangible with future experiments

By the term future experiments, we mean experiments that test societal possibilities. Future experiments can help to find out how the world of tomorrow could and should function.

Different futures are made tangible with experiments - and additionally in different forms. In London, for example, a future home has been set up that is radically adapted to the consequences of climate change. In the kitchen, mushrooms are grown, food is preserved and mealworms are cultivated. Visitors can experience what life in cities might feel like if the climate were to change drastically. This future experiment thus attempts to make the magnitude and complexity of climate change tangible, comprehensible and concrete.

Future experiment in the form of an exhibition: apartment adapted to climate change. Image: Superflux

But future experiments can also give hope. The Pura Verdura cooperative in the city of Zurich is testing a future with solidarity-based agriculture. Together with experienced gardeners, cooperative members grow their own vegetables and use their fields to promote biodiversity, which is essential in the context of the climate crisis.

Another bold experiment for the future is Ting, which is testing a future with basic income. In this community, 270 members finance each other's so-called "community basic incomes," which have been used to create projects to promote permaculture, food cooperatives, and sustainable menstrual products, among others.

The field of Pura Verdura, a cooperative that grows vegetables in the middle of the city of Zurich according to the principles of solidarity agriculture, conducting a strategic experiment on the future of food. Image: Pura Verdura

Another bold experiment for the future is Ting, which is testing a future with basic income. In this community, 270 members finance each other's so-called "community basic incomes," which have been used to create projects to promote permaculture, food cooperatives, and sustainable menstrual products, among others.

The characteristics of future experiments

Future experiments are always participatory. This means that as many different actors and perspectives as possible are involved.

In addition to the participatory character, transdisciplinarity also plays a decisive role. Future design should be build on knowledge, experience and methods from a wide range of disciplines and combine scientific and practical knowledge. Therefore, future experiments are ideally designed in a collaboration of the public and private sectors, civil society and the sciences.

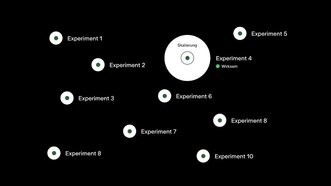

A single future experiment is not enough to bring about significant change - it is always necessary to think in terms of portfolios of experiments. This means that a vision (e.g., restoring biodiversity) should be approached with ten or more experiments in different ways.

Why is this worthwhile?

Experiment portfolios are composed of a variety of future experiments. Each experiment tests desirable futures in different ways, always with the goal of moving in the direction of the vision. Image: Dezentrum

The strengths of future experiments

Experiments test a solution approach on a small scale. Portfolios of future experiments increase the chance of finding solutions that are effective and can gain majority support. In addition, risks are minimized by testing a variety of solution approaches rather than relying on just one card.

Future experiments are cost-efficient because it is possible to find out in a short time whether a solution approach is effective or not. The approach is also significantly faster because future experiments can be implemented at the local level with fewer hurdles.

Since future experiments can be experienced concretely and take place in the present, they can be used to discuss and negotiate possible futures even without specialist expertise. This enables futures to be examined from different perspectives and critically scrutinized. With its participatory character, its majority capability is tested early on, and the polarization of the population is counteracted by the joint shaping of futures.

“Innovation comes from collective effort, not a narrow group of white men in California. If we want to solve the world’s biggest problems, we better understand that.” — Mariana Mazzucato

Just as in the above quote from economist Mariana Mazzucato, the same applies to innovation around the climate crisis: only together, with the population, can the necessary change be achieved sustainably.

Future experiments require courageous visions

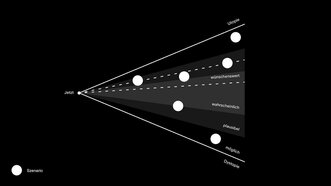

The starting point for effective future experiments is the development of shared visions. To establish these, we can work with scenarios: Which futures do we find desirable?

The scenario technique as an aid to developing visions. Image: Dezentrum

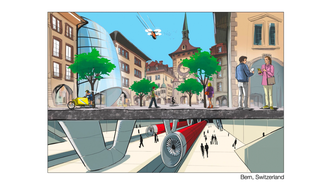

In the Expedition Future Policy Sprint, for example, possible future scenarios were visualized by means of megatrends, studies and political plans for climate-neutral mobility in 2050.

Is this what a desirable future looks like in Bern? Expedition Zukunft and Dezentrum have drawn up five future scenarios and discussed them with participants from parliament, administration, science, civil society and the private sector. Image: Expedition Future

These scenarios form a basis for the discourse around our future and help to find a common vision. Paris, for example, has adopted a vision of a "15-minute city" and the gradual elimination of vehicles. Anne Hidalgo, mayor of Paris, explains the project this way:

“My project is about proximity, participation, collaboration and ecology. In Paris we all feel we have no time, we are always rushing to one place or another, always trying to gain time. That is why I am convinced we need to transform the city so Parisians can learn, do sports, have healthcare, shop, within 15 minutes of their home.”

Once a shared vision has been formulated, it is broken down into a portfolio of future experiments. What measures could be used to achieve the vision? What experiments are necessary and useful to test these measures? Each future experiment has clear objectives, which can be used to continuously check whether the experiment is having an effect or not. If an experiment is effective, it should be expanded geographically or structurally. In this way, the effect of the solution approach is multiplied and the vision comes ever closer.

If an experiment from the portfolio is confirmed to be effective, it is scaled up. Image: Dezentrum

How Swiss cities can become pioneers

Swiss cities offer ideal conditions for future experiments. Strong science, innovative companies, a committed civil society and experience from participatory projects are among Switzerland's strengths. Together, they have the potential to develop pioneering solutions that inspire internationally and drive the necessary change.

The North is already showing how it can be done. Helsinki, for example, has established testbeds where new products and services are developed and tested under real-world conditions in collaboration with businesses, municipal employees, end users, universities, technical colleges and research institutes.

Why not testbeds in Swiss cities? The future can be shaped. It must not just be thought about, but made. The probability that we will end up in the future we all want becomes greater with future experiments.

About Meso

Meso is an alliance of organizations that want to tackle the creation of a sustainable future together.

Funding partner: Mercator Foundation Switzerland

More Readings

- «Das Neue neu denken» by Dominic Hofstetter about a new understanding of innovation. Zum Artikel

- Björn Müller, PhD and Ivo Nicholas Scherrer about den Begriff «systemische Innovation». Zum Artikel